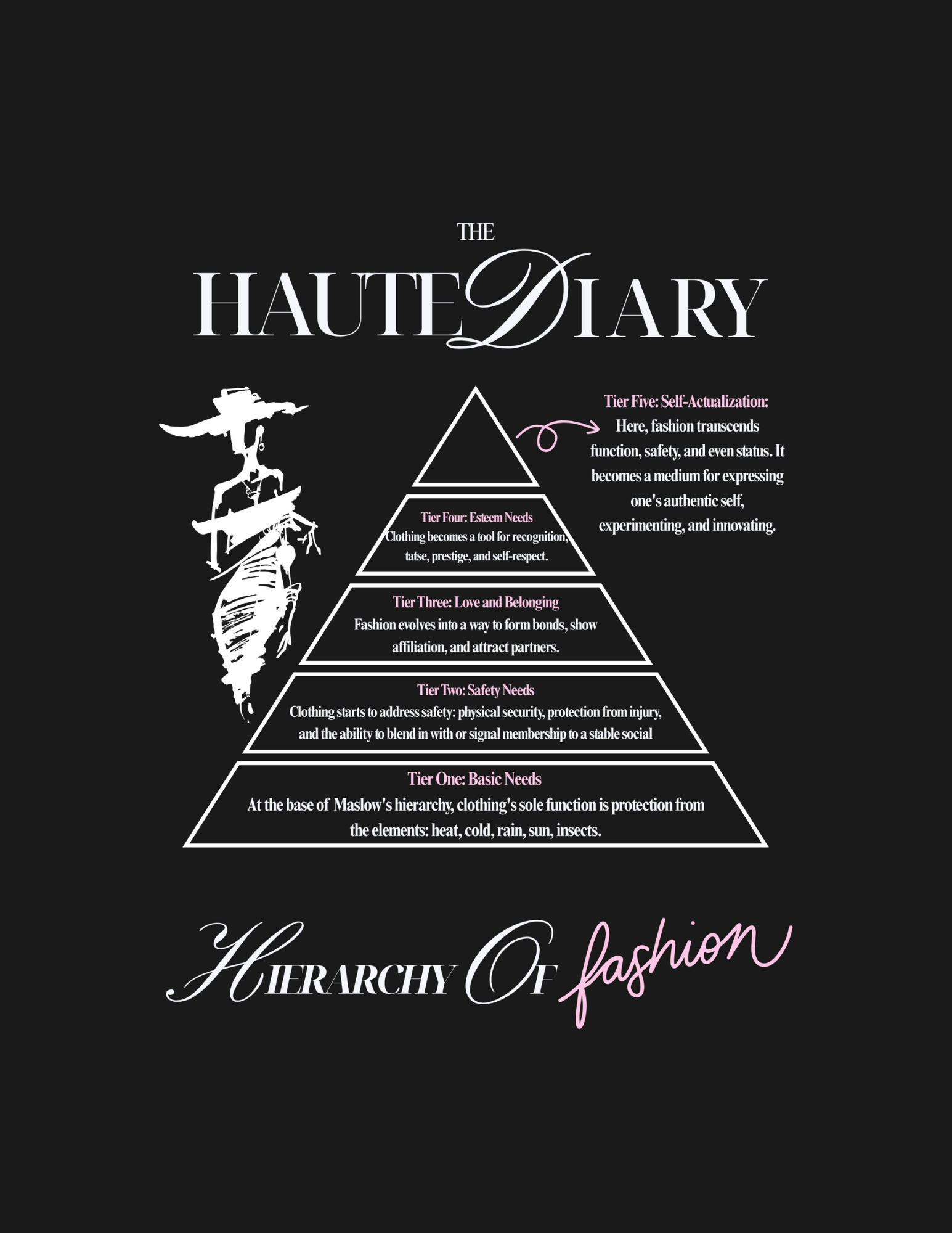

The Haute Diary’s Hierarchy of Fashion

Fashion and psychology are far more intertwined than we might assume. Psychology, quite literally, is the study of the mind, and fashion, as a reflection of human behavior, desire, and identity, offers a compelling lens through which to view it.

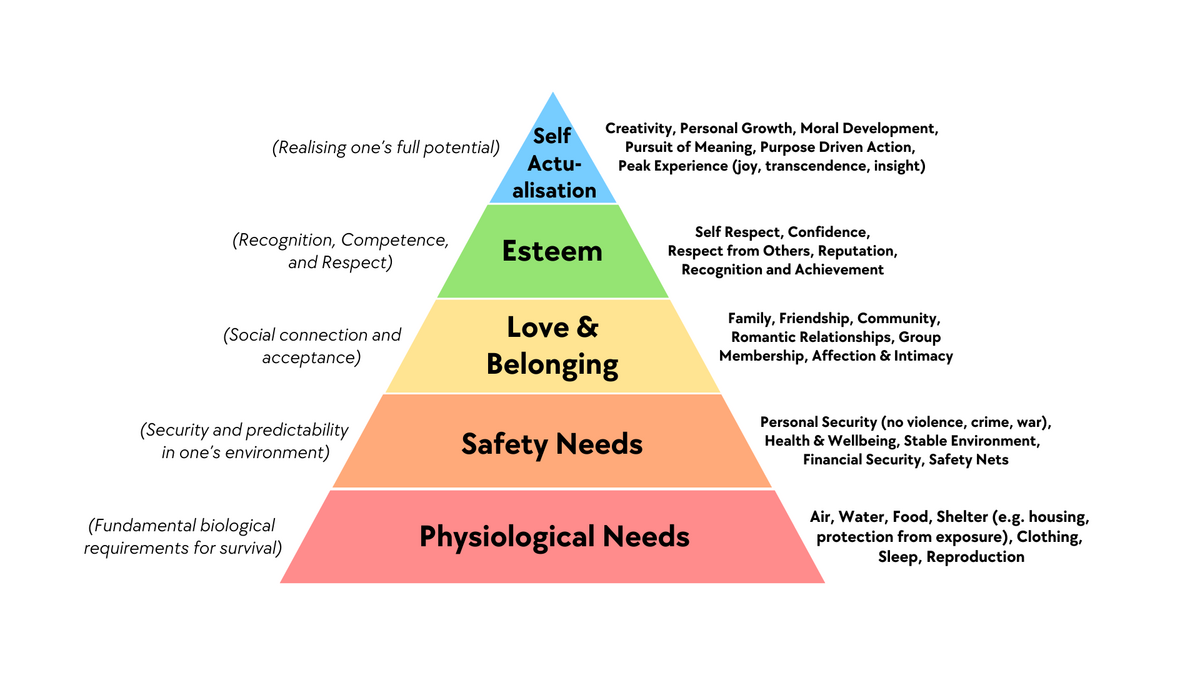

One of the most insightful frameworks for understanding this connection is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Originally developed as a theory of human motivation, it outlines how people prioritize their needs in a progression from basic survival to self-actualization. When applied to fashion, this framework reveals how clothing has evolved from a matter of necessity to a medium for expression, belonging, and personal fulfillment.

Understanding the Theory

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy is often depicted as a pyramid, with each tier representing a category of human needs. At the base are the most fundamental: physiological requirements such as food, water, and shelter. Only when these are satisfied do we move upward toward safety, social belonging, esteem, and finally, self-actualization, which is the realization of our fullest potential.

In practical terms, when you are cold, hungry, or exhausted, your priority is meeting those immediate needs. Dressing to project identity or to make a creative statement is unlikely to matter until those essentials are handled. Conversely, when survival and stability are secured, clothing becomes a tool for signaling belonging, projecting confidence, and even embodying one’s personal philosophy.

Fashion at Each Tier

1. Physiological Needs: Clothing for Survival

At its most fundamental, clothing functions as protection: insulation against cold, shielding from heat, and defense from environmental hazards. Historically, this meant furs, leathers, and basic woven fabrics designed for function over form. Even today, thermal layers, weatherproof outerwear, and work uniforms speak to this primal purpose.

2. Safety Needs: Security and Stability in Dress

Once survival is handled, clothing begins to serve as a safeguard for both body and social position. Historically, armor, protective workwear, and durable fabrics filled this role. In contemporary contexts, the equivalent might be corporate dress codes, uniforms, or even the unspoken style rules that help one “fit in” within a professional or cultural environment. Clothing here becomes a form of social armor.

3. Love and Belonging: Fashion as Connection

This is where fashion becomes social currency. Clothing communicates affiliation through subcultural style codes, shared trends, and group identifiers. From punk leather jackets to matching sorority apparel to the coordinated aesthetics of streetwear crews, fashion at this level is about signaling who you are aligned with and, by extension, who you are not.

4. Esteem Needs: Fashion as Status and Recognition

Once belonging is secured, clothing becomes a means of earning respect from others and reinforcing self-confidence. Throughout history, luxury garments, exclusive fabrics, and designer labels have served as status symbols. In modern times, a tailored suit, a rare sneaker drop, or a limited-edition handbag can function as both a personal achievement marker and a public display of success. Fashion at this stage is about the psychological reinforcement that comes from recognition, authority, and accomplishment.

5. Self-Actualization: Fashion as Self-Expression and Purpose

At the highest tier, fashion becomes a pure creative outlet, untethered from the constraints of function, safety, or status. This is the realm of avant-garde design, personal style experimentation, and meaningful sartorial choices that reflect one’s authentic identity. Here, dressing is not about impressing others but about embodying a personal vision. It can mean upcycling garments as a sustainability statement, mixing couture with thrifted finds to tell a personal story, or breaking gender norms through clothing choices.

The Overlap in Modern Life

While Maslow’s theory suggests a linear climb from one need to the next, the modern fashion landscape allows for overlap. A single outfit can address multiple tiers. A well-made coat may provide warmth (physiological), adhere to workplace norms (safety), align with a friend group’s style (belonging), carry a luxury label (esteem), and still express personal creativity (self-actualization).

Fashion, in this sense, is not simply about what we wear. Think of your style as a visual language, a social signal, and an emotional anchor that evolves with our needs. Understanding it through Maslow’s hierarchy offers a deeper appreciation of the psychology woven into every garment.